Many people think that being smart is something you’re either born with or not. But is it really their genes, or is their technique that makes the difference between smart and average? In this guide, you will learn the steps needed to increase your ability to learn by 10x, and make your friends and colleagues wonder how you became such as smart person. These are not some quick hacks you can find on YouTube. This is a comprehensive framework based on cognitive science.

Guide created by Dominic Zijlstra (Founder of Traverse)

Table of Contents

A flop or a giant leap?The Fosbury Flop of LearningDangerous Myths about Learning❌ Your learning is limited by your memory and IQ❌ More = better.My own Fosbury FlopHow do I learn faster and remember more?The FoundationThe Learning Process in your Brain4 Principles of Effective LearningCommon techniques that are a waste of timeHighlighting and re-readingVerbatim, instant note-takingFlashcard practice (unvaried)The 10x Learning Framework0. Pre-study1. Ingest Information2. Encoding3. Consolidation4. Retrieval5. ReconsolidationYour Training Schema for SuccessLifestylePlanningMake reflection part of the processHabits and ConsistencyProcrastinationFocusTraining your brain muscleRecapWhat you should do next

A flop or a giant leap?

What is the Fosbury Flop, and how does it relate to learning?

In the 1950’s, Dick Fosbury grew up in a small town in Oregon. As a teenager, he experienced a personal tragedy: He and his brother Greg were riding a bike and a drunk truck driver killed his brother.

It devastated the family and led to his parents’ divorce. Dick was near depression but found solace in sports: he had joined the high school team as a high jumper. However, he struggled to clear the bar at the minimum height required to compete (5 feet or 1.5 m). He and the rest of the team were using a variant of the traditional ‘roll’ technique, whereby a jumper goes feet-first, head-down over the bar.

After failing time after time, Dick instinctively developed a new technique, jumping with his back towards the bar. This allowed him to keep his center of mass below it, so he could spend less energy while clearing higher bars.

With this new technique, Dick easily cleared the minimum height, and soon began winning competitions for his team. The technique’s weird appearance, and back-first landing caught the attention of a local newspaper, who dubbed the technique the Fosbury Flop. A name not without ridicule - and local coaches warned about the danger of back landings.

However, Dick remained undeterred, and his jumping results got him an athletic scholarship at the Oregon State University.

His coach convinced him to turn back to the traditional roll technique for college competitions. However, following that advice, Fosbury jumped inconsistently. He nearly lost his scholarship, and his grades suffered as well.

Fosbury went back to his own technique, and in 1968 finally broke through - and qualified for the US Olympic team with a personal best of 2.20m.

At the Olympics in Mexico City, Fosbury’s technique got plenty of attention from the crowd - and not undeserved. He took the gold medal and set a new Olympic record of 2.24m.

Was Fosbury a great athlete? Or an average athlete with an extraordinary technique?

The 1972 Olympic games in Munich provide the answer: 28 of the 40 competitors used the Fosbury Flop.

And Fosbury himself? He was no longer able to compete, but he founded a successful engineering firm and has been an advocate for youth sports ever since.

The Fosbury Flop of Learning

Like Fosbury was struggling to achieve athletic results using the ‘standard method’, you may be struggling to get excellent academic results using ‘best learning practices’. All the while looking at peers you consider extremely smart, and who seem to get great grades without putting in too much effort.

But what if these extremely smart peers are not extraordinary mind athletes? What if, whether intentionally or by accident, they just came across the Fosbury Flop of learning, while you are still rolling along with the mediocre majority of students?

This guide will reveal what the Fosbury Flop of Learning is, and how you can retrain your brain to flop and use it to jump higher, achieve great academic results, look smart (no, actually be smart) in front of your peers, without the need for an extraordinary IQ, and while spending less time studying.

Dangerous Myths about Learning

Sounds incredible?

If you’ve spent most of your life in an education system where virtually nobody knows what effective learning is, and hence give you well-intended but misleading and even dangerous advice, you’ve likely come to believe quite a few things that are outright wrong and devastating for your learning experience. Let’s tackle some of those first, and open your mind to learn how to flop.

❌ Your learning is limited by your memory and IQ

From a young age on, we are constantly being graded. Divided into ‘good students’ and ‘bad students’. Or ‘good at math’ and ‘bad at math’, …

This may lead you to believe that that is just the group in which you belong.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Imagine if Dick Fosbury, when struggling to clear the minimum height bar, thought that that was just where he belonged? He would never have discovered the Fosbury flop, and would never have won Olympic gold.

Just like Fosbury, you can retrain your brain to use effective techniques, and achieve more than you ever imagined possible.

It is not your IQ that counts, it is how you learn that makes all the difference.¹⁾

❌ More = better.

You just need to study more hours.

Take more notes.

Review more flashcards.

Repeat, repeat, repeat.

This is another dangerous misconception.²⁾ The truth is, most if not all actual learning happens in those moments where you are doing nothing. When you are taking a walk and it suddenly clicks. When you are in the shower and suddenly have an AHA-moment.³⁾

When you just try to cram more hours of study into your day, you remove all room for your brain to process and actually learn.

And not only will you not learn, you will also constantly be overwhelmed. Overwhelmed by all the notes you take (which you don’t remember a few hours later). Overwhelmed by an enormous load of flashcard reviews every day.

It’s not only destructive for your learning, but also for your motivation, your critical thinking and your natural human curiosity. It actively is the opposite of learning.⁴⁾

In this guide, I’ll teach you how to spend less time studying, with more joy and vastly superior learning (and academic) results.

My own Fosbury Flop

My name is Dominic Zijlstra. I’m an edTech entrepreneur.

5 years ago I thought I was pretty smart. I had studied physics in Germany and in Brazil. I’d worked for Airbus as a spacecraft engineer, and as a data scientist for a London fintech startup.

Then I met my wife, who is Chinese. But I couldn’t communicate with her parents, because they didn’t speak English.

So I set out to learn Mandarin Chinese. But it was impossible. There are thousands of characters, all connected in complex ways. There was some kind of order to it but I couldn’t discern it.

This was my big realization that although I thought I was pretty smart, actually my learning methods were weak.

It prompted me to dive deep into the science of learning. I came across methods like spaced repetition and active recall. It worked, but it was still slow and tedious. The famous Elon Musk quote about building trees of knowledge brought me on the path to discovering the best approach to learning. Based on the principle of encoding, this method was joyful, helped me see the big picture, and must importantly, it actually worked. Using this method, I was able to learn Chinese successfully, live in China and chat with my wife’s family and friends.

Ok, good for me!

But how do I know I’m an average ‘Fosbury’ with a great technique, rather than an inimitable genius?

I codified my learning method into an online learning tool - initially built to help myself learn Mandarin. Soon, the tool was picked up by learners in many other fields like medicine, languages, technical skills, marketing, psychology and more.

Take Raleigh Sorbonne for example. He was studying for the MCAT, a 6-hour exam to enter medical school. After researching dozens of tools, he had the strong feeling that there had to be a better way to learn. Finally, when coming across my method, he was able to study more efficiently than ever before, while saving time and having more fun in the process. When he took the test, he got a 99th percentile score.

So I have seen this method work for myself and others, and I know that it will help you as well, which is the reason that I’ve written it down in this format for your benefit.

(One of my advisors in developing the method and the tool is Dr Justin Sung, a study coach with 10+ years of experience helping students learn better. If you prefer to learn by watching video rather than by reading, I’d suggest watching his YouTube channel, which conveys similar ideas.)

Let’s dive right into the matter.

How do I learn faster and remember more?

Like a sports technique, you need to go through several steps to master the optimal learning framework:

- Get into shape

- Learn how our body (in this case, our brain) works

- Learn the new technique

- Set up a training schema to successfully master the technique and bring it into practice

This guide will take you through all the steps.

The Foundation

Great, now we’re ready to do our first bit of learning. This is all about what happens in the brain when you learn, as understood by the latest neuroscience.

Having this knowledge will help you identify where you’re at right now (the next section) and why the method we will teach you delivers such extraordinary results. It’s important to do this bit of meta-learning, as it will kick off a flywheel that allows you to keep improving yourself for the rest of your life.

The Learning Process in your Brain

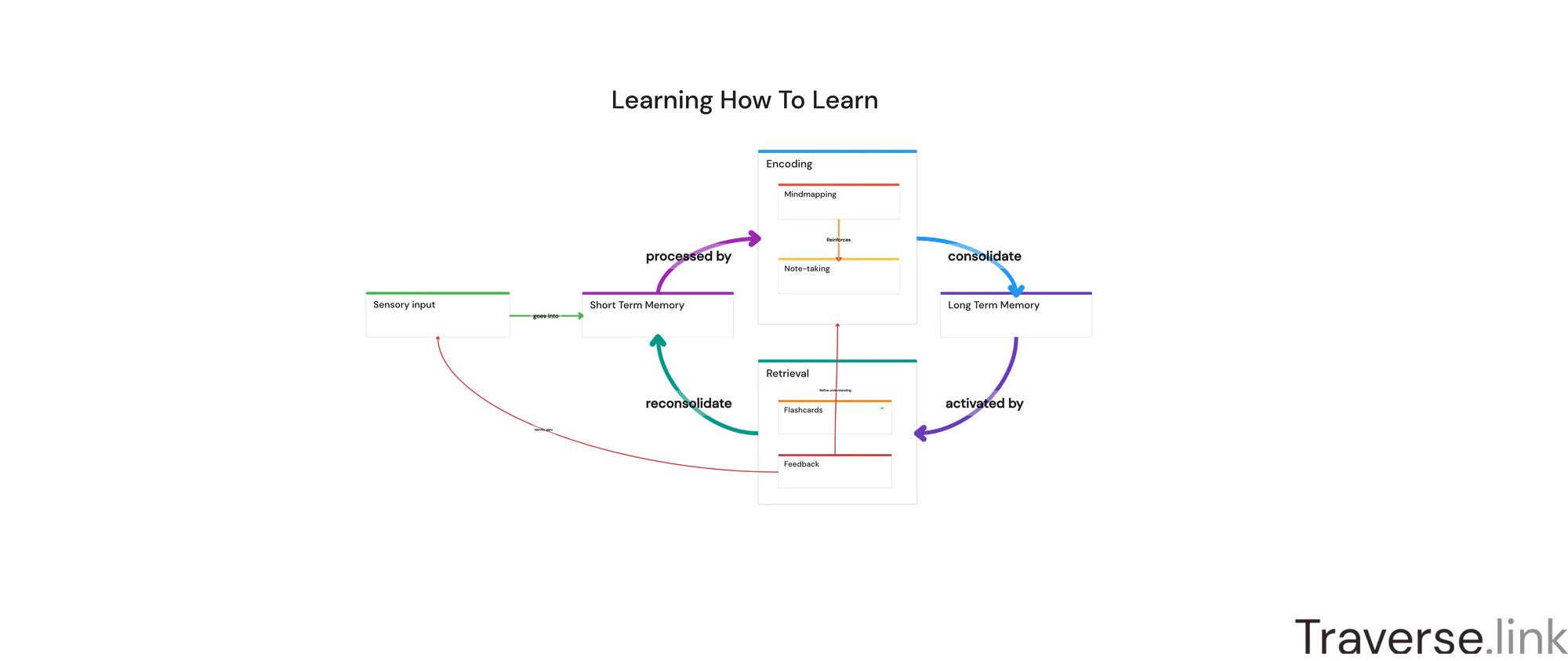

At a high level, these are the 5 steps your brain goes through when you learn⁵⁾:

- Ingest information

You read a textbook or research paper, watch a YouTube video, or attend a lecture. This information then goes into short-term or working memory (STM). 99% of information is immediately discarded and forgotten, which is a good thing (you don’t want to remember the color of your professor’s socks on May 13th last year). In fact, our STM can only hold 7 items at the same time.⁶⁾

- Encoding

The items that we do want to remember, need to be encoded. Encoding means creating a mental representation of the information, which can be stored into long-term memory (LTM). Humans are both curious and sense-making creatures: only mental representations that follow a certain logic and are deemed interesting can be successfully stored into LTM.⁷⁾

- Consolidation

Consolidation is the step of actually moving the mental representations into long-term memory. Your brain replays the lesson and straightens out gaps. It then finds a suitable place to store it in LTM by connecting it to your prior knowledge and experiences. This process takes hours or days, and takes place during breaks and sleep.⁷⁾

- Retrieval

The goal of learning is to apply what you’ve learned - whether in an exam or in your job. This requires creating cues to retrieve the information, possibly refining how it is connected to your prior knowledge, so that the right cue is triggered at the right time (similar to habit-forming cues!). The more and better cues you have, the better you’re able to recall the information and use it in different situations when it’s needed.⁸⁾

- Reconsolidation

Every time you retrieve information, it is reconsolidated. The experience of retrieval is attached to that information and strengthens connections. If you retrieve the information in many different contexts, you will make a lot of connections, whereas if you always retrieve it the same way, any other possible connections are dulled. This ultimately determines your ability to process information in different contexts.⁹⁾

4 Principles of Effective Learning

From this simple process description, we can derive four core principles which help us explain why some learning techniques work and others don’t. These principles will appear again and again as we go through the actual techniques.

- The right encoding makes the difference between remembering and forgetting

The Encoding step in the above process is often neglected, even though it is by far the most important step¹⁰⁾. But it is also the most difficult one to get right. Encode the information into mental representations that make sense, and you’re well on your way to building a strong memory. Skip over proper encoding, and the information will be no more than isolated facts. With nothing to cling onto they are quickly forgotten.

So, how do we encode information well?

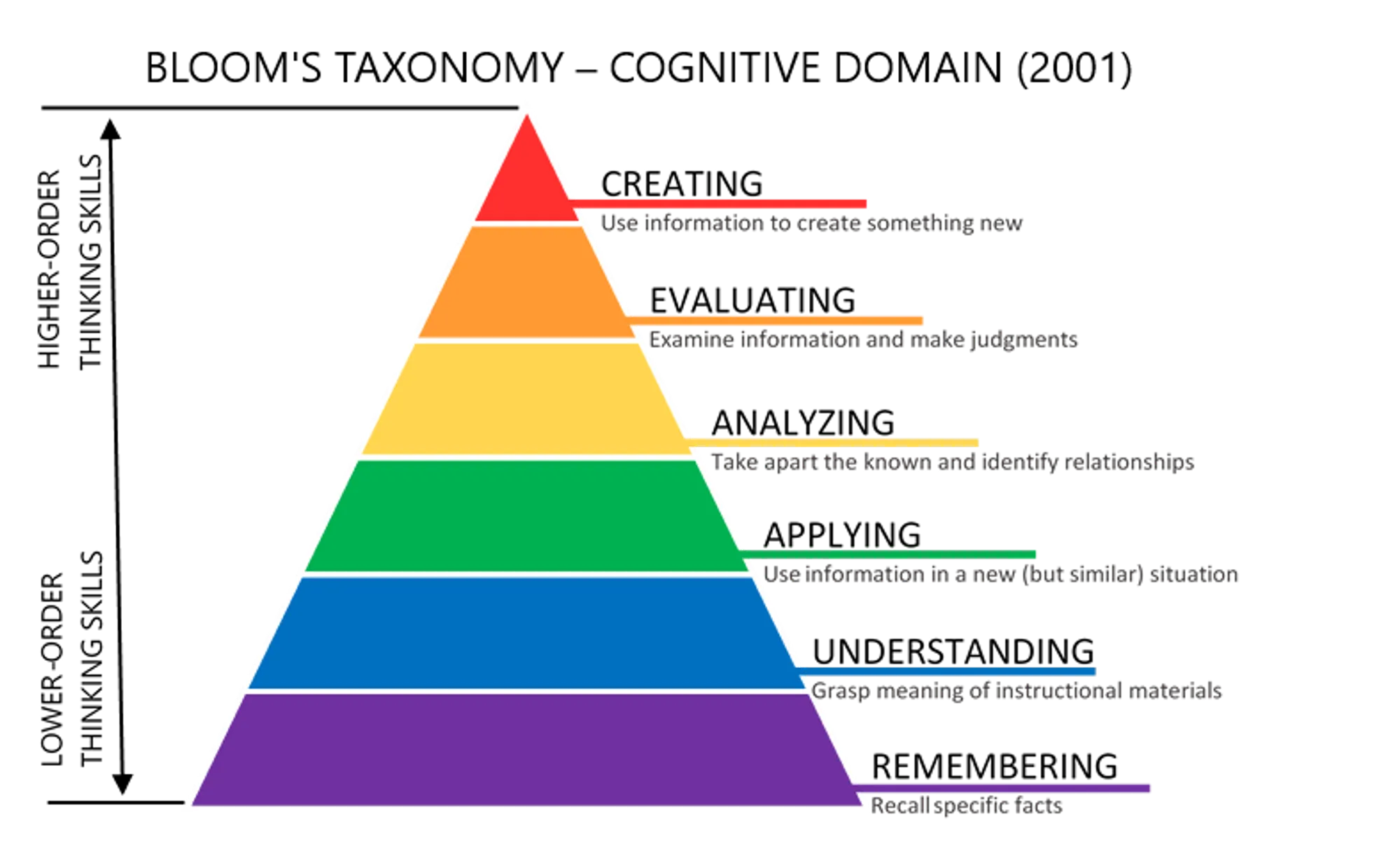

In short, good encoding = higher-order thinking¹¹⁾.

Ok, what do we mean by higher-order thinking? It’s a concept developed by learning scientist Benjamin Bloom, who developed the Bloom’s Taxonomy of learning¹²⁾:

Right at the bottom we see skills which are usually associated with learning, such as remembering and understanding. Bloom’s insight was, that focusing on those lower-order thinking skills actually leads to poor encoding, and hence poor retention of new knowledge.¹¹⁾

If you’ve ever tried to memorize a lot of meaningless information by rote (such as a definitions list of an unfamiliar field), you will know what he’s talking about. Focusing exclusively on memory leads to poor learning outcomes - and actually blocks higher order thinking.

Focusing on understanding is only slightly better - once you understand a concept it still lives in isolation and is at danger of being forgotten.

Bloom’s taxonomy suggests the opposite approach: focus straight away on higher order thinking skills like analyzing, evaluating and creating. Your brain automatically fills in the lower orders.¹¹⁾

In our 10x Learning Method section below, we will see what higher order thinking looks like in practice.

- Deep processing makes the difference between comprehension and ignorance

Closely related to encoding is deep processing. Encoding occurs early on in the learning process, and helps build a strong long term memory structure. Deep processing occurs later on, in the retrieval and reconsolidation phases.

It means retrieving our newly-learnt knowledge, using it in a new context, and restoring it into long term memory in a more strongly connected form. In common language, we’d say that encoding builds strong memory, while deep processing builds strong comprehension.

Lower order retrieval techniques make you retrieve the information in the same context on every review. You may have experienced this if you ever reviewed a flashcard and already knew the answer before even reading to the end. You think you’ve really learned the concept but actually it’s just an automatic response primed by a single cue (the words on the card). By contrast, deep processing ensures that we can recall and apply the information in many different contexts, deep processing ensures that we can recall and apply the information in many different contexts.

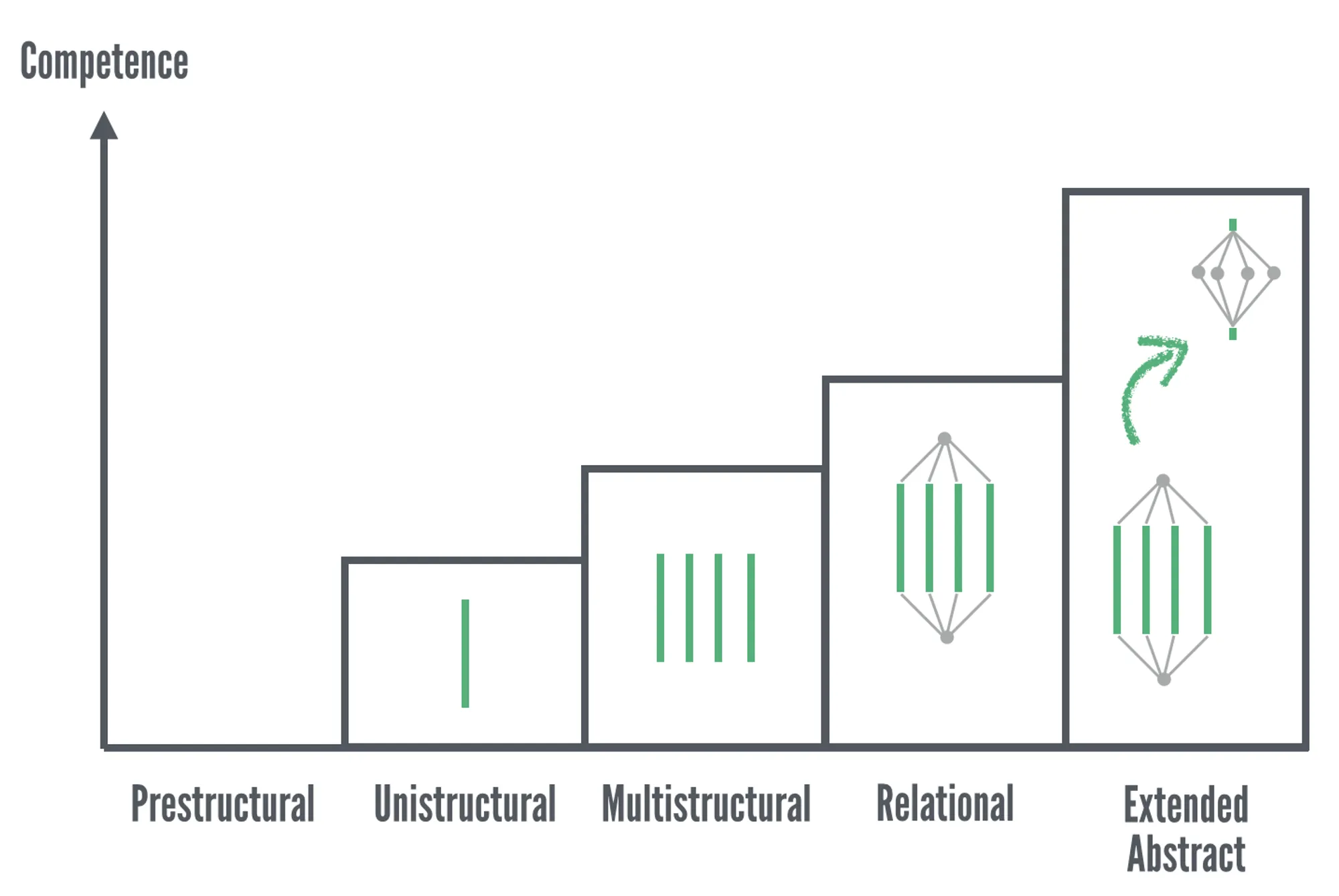

To practice deep processing, we follow SOLO taxonomy, which is closely related to Bloom’s taxonomy above:

As you can see, instead of learning in isolation (unistructural), instead we want to group things together (multistructural), or even better, focus on discovering connections, rules and structures about how things work (relational), and finally thinking in systems, and building mental models that explain how the world works (extended abstract).¹³⁾

These activities can be quite taxing for the untrained brain. More precisely, these activities have a high cognitive load. Cognitive load theory states that learning increases as cognitive load increases.¹⁴⁾

In the 10x Learning Method section, you will learn how to do deep processing in practice, and in the Training Schema section, you’ll see how you can train your brain to have a higher cognitive load tolerance.

- Learning is a flywheel

All this higher order thinking sounds like a lot of work. And it is, especially in the beginning. On top of that, it takes time for the effect to show in your learning.

It is a time investment in the short term, which only pays off in the long term. But once it starts paying off, it increases your capacity to learn exponentially. Think about it like this: if you’ve encoded and deeply processed one topic, that topic provides a lot of entry points to which you can attach new information from another topic. So encoding and deeply processing the next topic becomes easier as you have more and more to cling onto.⁹⁾

Whereas, if you keep learning shallowly as you may be doing currently, you will never have a strong base to build on, and while it may feel easy now, you’re setting yourself up for failure in the long run.

In the Training Schema section, we will talk about how you can set up your systems to make it through this tough initial phase, and build a learning flywheel which eventually propels itself.

Learning in isolation:

Vs building a learning flywheel you can connect to:

- Boredom and fatigue are the enemies of successful learning

Many common learning activities, such as copiously taking notes, and endlessly reviewing flashcards, are popular because they’re easy to explain, and easy to execute.¹⁵⁾

But they invariably get boring quickly, because they operate at low orders of thinking. Low orders of thinking are not only ineffective, they are also not intellectually stimulating. Higher order thinking means variation, discovery and challenging yourself.

Sounds almost like a video game, right? Once you get the hang of it, it can be a lot of fun. You’ll jump from one AHA-moment to another, exploring your natural curiosity. It turns out learning is a highly creative process.

And when you get tired, you give your brain a break, so it can process all the information. That way, focused and diffused brain modes collaborate to produce the best learning.³⁾

Common techniques that are a waste of time

The majority of learners are rollers (see the Fosbury flop story): they use learning techniques that everyone uses, without thinking much about whether there might be better ways¹⁶⁾. As a result, they are outrun again and again by the Fosbury floppers who have intentionally reflected on their learning and come up with better, and unconventional, ways.

If you’re using one or more of the techniques below, you are likely still rolling:

Highlighting and re-reading

Highlighting and re-reading important passages feels productive. But they are very shallow activities, and merely give you the illusion that you’re learning¹⁷⁾¹⁹⁾. Moreover, they take up mental bandwidth which distracts from the actual learning material.

Verbatim, instant note-taking

Instantly taking notes, similar to highlighting, is a very superficial activity. You copy what was said word-by-word, or paraphrase. Again, it can feel effective, but how often do you look back at your notes only to realize you didn’t understand much of the lecture?

Instant note-taking is a widespread habit among many students¹⁷⁾, but you’ll have to unlearn it in order to 10x your learning. Just like those roll jumpers had to unlearn their jumping technique as their competitors switched over to the superior Fosbury flop.

Flashcard practice (unvaried)

Flashcard practice, especially when using spaced repetition, uses the spacing effect and the testing effect to improve your recall of information.

However, most students relying on flashcard practice don’t take the time to properly encode the information in the first place¹⁶⁾. This is especially true when just using someone else’s flashcard deck without making it your own.

Lack of encoding means that a lot of repetitions are required to make it stick²⁰⁾, and even then you will only be able to retrieve the information in a very limited context.¹⁸⁾

In the 10x Learning Method section, you’ll learn how you can use the principles of spaced repetition and active recall in a way that does produce effective and deep learning.

But no worries if you have made a habit of using some of these ineffective techniques. Your brain is extremely plastic, which means it can be retrained (this is called neuroplasticity). First, you’ll need to unlearn bad habits, so that they can be replaced by effective study habits. Although complete retraining can take several months, once done the benefits stay with you for life. By any definition, you will become a smarter person.

We will take you through all of the steps in the next section.

The 10x Learning Framework

With our knowledge of how the learning process works, and the core principles we derived from it, we can now improve learning at every step (there are 6 in total, the 5 steps from the learning process, preceded by a pre-study step) . If we improve our learning at every step by just 50%, the improvements compound to a 10x overall improvement in learning. (In reality, at some of the steps, like encoding, we can easily achieve an improvement far bigger than 50%.)

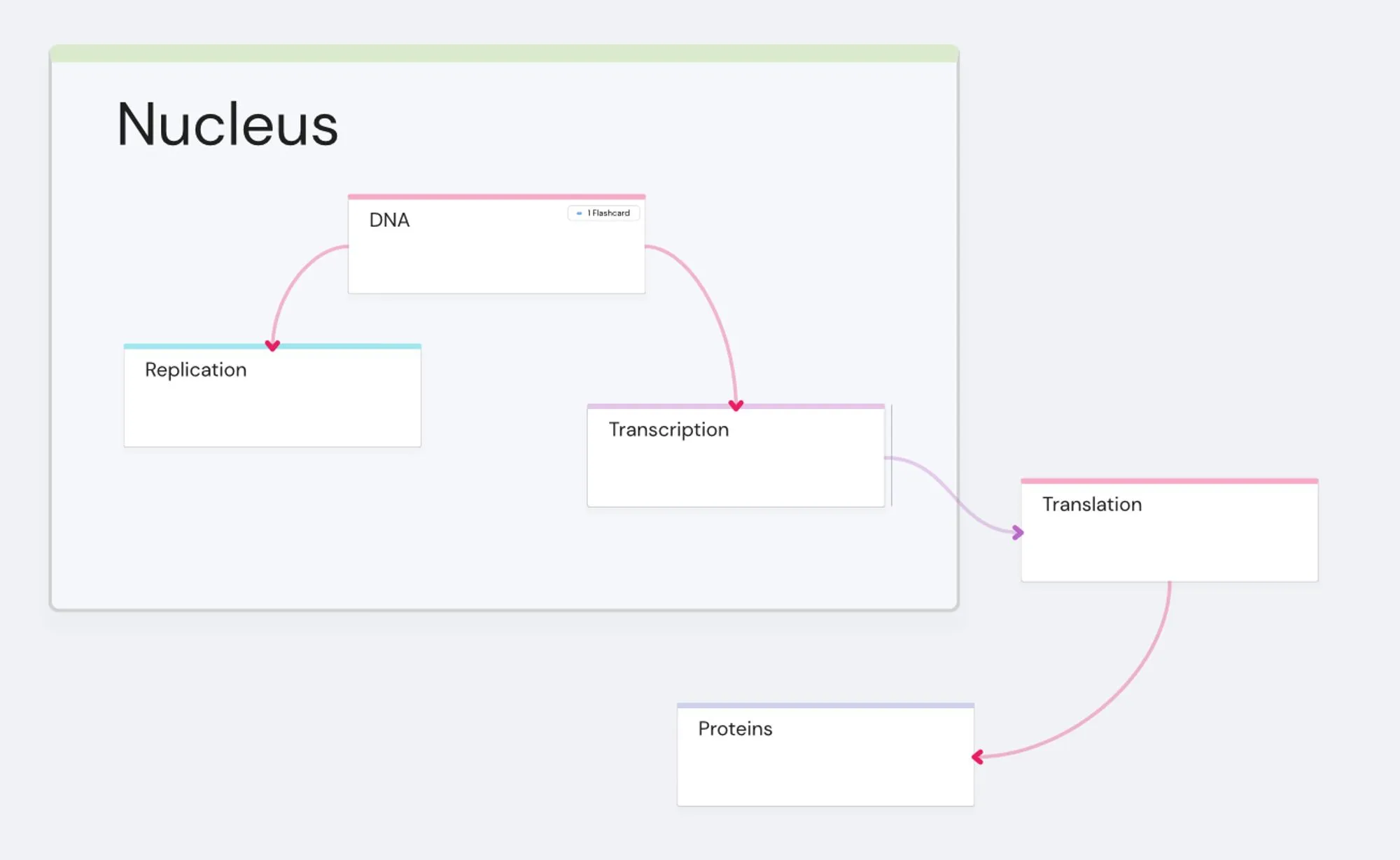

As an example throughout these steps, I’ll highlight how to learn the central dogma of biology which is how proteins are created from DNA. (This is a foundational topic for the MCAT.)

0. Pre-study

Pre-study is the work you do before actually ingesting the information, e.g. prior to the lecture or opening the text book.

Even students already doing pre-study, often just do the same activities that they’d do after the lecture. It is much more effective to do specific pre-study activities which help prepare your brain to absorb new information. This is like an athlete visualizing their jump before they actually start running.

Level 1: Identify the 3-4 main ideas of the topic you’re going to study. If you have no clue, try digging into your prior knowledge, or skim a text book on the topic.

Example: After reading my textbook I write down “Central Dogma” (whatever the heck that is) and “DNA” and “protein”

Level 2: Identify the relationships between the 3-4 main ideas. This helps your brain get used to deep processing and becoming fluent with ideas.

Example: I recognize that “Central Dogma” is the umbrella term for DNA converted to Protein. So I draw a line connecting DNA to Protein.

Level 3: Branch out further. For every one of the main ideas, find another 2-3 sub-ideas within that main idea.

Example: I learn DNA is related to replication so I draw a line connecting “DNA” and transcription. I also learn Proteins are related to mRNA so I connect those two ideas with a line.

Level 4: Connect to your prior knowledge and experiences. This resembles doing a brain dump.

Example: Okay so I’ve heard of protein before from my nutrition class. I know protein builds muscles, so I connect the word “muscles” to “protein”

Level 5: Ask questions (inquiry-based learning³⁰⁾). What are the questions around these ideas that you are curious about, and which you’d like to see answered during your study? Which clues do you already have for the answers?³⁹⁾

Example: My biggest question is how are Transcription and mRNA related, if they are related at all? I’m guessing they will be.

Level 6: Try solving some of the practice problems about the topic before you actually know the method, formula etc. This helps you identify challenges and focuses your attention later on. This is called generative learning, as it helps you generate ideas and hypothesis by yourself before you learn them form others (it’s like doing science!).⁷⁾

Example: I quickly try my best bet at answering two of the end of chapter questions

1. Ingest Information

The biggest improvement you can make when ingesting information (e.g. reading a book or attending a lecture), is eliminating a bad habit you may have: stop taking notes immediately.

If you take notes immediately, you are just copying word for word (or paraphrasing) what the professor said. Similarly, if you’re reading a book, do not highlight things as you read. Both of these activities are lower order thinking. They feel like work, so they may give you the illusion that you are learning well¹⁵⁾. But actually they distract your attention from the actual material. How many times have you looked back at your lecture notes only to find out that you barely remember anything?

Instead, open yourself up completely to the book or lecture. Absorb the information in your head. This may feel uncomfortable at first, because there’s probably too much information to hold at once. But it is exactly this feeling of discomfort which indicates that your brain is doing the hard work required to learn. It prioritizes the new information, tries to make sense of it.

When you take notes, you offload this information onto paper. You’re telling your brain not to worry about it. This may provide some temporary relief, but it ultimately causes you to have much more work to do later on as you look back at your notes¹⁵⁾.

Get comfortable in the discomfort. Like the athlete at the moment of jumping, just feel the sensation, and you will develop an intuition for the topic.

This habit can be extremely hard to get rid of, so again we’ve divided this into levels to make it easier for you:

Level 1: Instead of taking notes word for word, or highlighting whole sentences, just make quick summary notes every few minutes, writing down the main ideas.

Example: I’m learning about Transcription and take notes every paragraph

Level 2: Make the intervals longer. Move from taking notes every 1-2 minutes to 5-10 minutes. Let the information simmer in your brain a bit longer.

Example: Now I’m taking notes every page instead of every paragraph. The notes are bigger picture.

Level 3: Only take notes at the very end of the lecture or your reading session. Summarize what you’ve absorbed.

Example: After reading full section on Transcription I write down a synthesis of what I learned. That is simple but highlights connections. Has an example as well to help.

Level 4: Delayed note-taking. Don’t take any notes until at least a few hours later.

Example: I do the same thing as above but hours later.

Level 5: Delayed mapping. Instead of taking notes, you will just rely on the encoding process described below.

Example:

2. Encoding

As mentioned in the Foundation, encoding is the most-overlooked and most challenging step in the learning process.

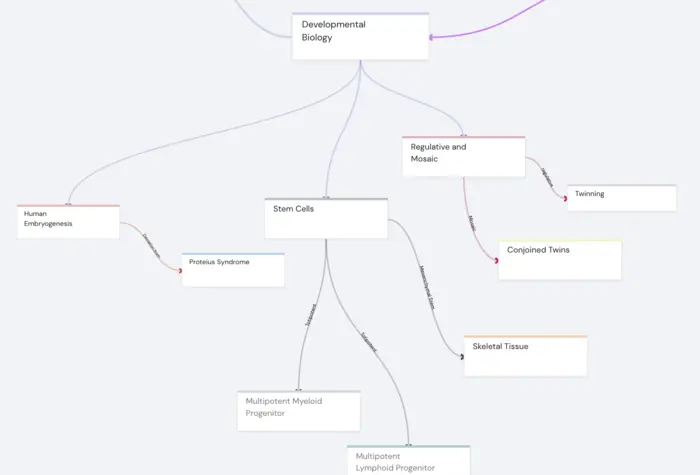

Luckily, there is an existing activity which can be adapted to produce extremely effective encoding.

That is the activity of mind mapping²⁹⁾³²⁾³³⁾, popularized in 1974 by Tony Buzan’s book Use Your Head²¹⁾. However, there are lots of ways of doing mind mapping. You may even have tried some before, and maybe found that it didn’t work for you. Most likely, you were not doing it right. Mind mapping the right way (that is, the way that leads to extremely effective encoding) is hard. Here, we’ll tell you step by step how to get there.

As always, take it one level at a time. This gives your brain time to adapt to your new learning practices. The brain doesn’t like to change it’s habits, so making the changes small enough that your brain doesn’t notice is necessary for successfully making the habit stick in the long term (this is the principle the Japanese call Kaizen).

Wait at least a few hours after ingesting the information before starting the encoding process. This gives your brain time to make sense of the information so that encoding it correctly into memory structures becomes much easier.

Make sure you have a place to draw your mind map. This can be a large sheet of paper, or a digital tool like Miro or Traverse. At each level, your mind map will become more refined, and more closely represents what is happening in your mind. Things start to become more logical, make more sense, and you can juggle them around in your mind more fluently.

Level 1: Chunking. Write the main topic in the center. Then, identify the main groups or chunks of information within the topic, and draw those around the main topic²²⁾. This is similar to what you did in the pre-study step, and provides corrective feedback.

Level 2: Growing your Knowledge Tree. Inside each chunk, draw out its main ideas. If these ideas can be divided into sub-ideas, feel free to branch out as deeply as you like.

Level 3: Linking your Thinking. Reflect on how the ideas connect, both with each other, as well as the connections inside each idea, as well as connections with other topics you already know. Here, our thinking really starts to become higher-order.

Level 4: Make it Visual. Instead of using words, try to make every idea as visual as possible. Create sketches to demonstrate a principle. It doesn’t matter if you can’t draw - it doesn’t need to look pretty. This helps you structure the information in your brain²³⁾. What matters is what ends up in your brain, not what ends up on paper. A great way of visualizing ideas is coming up with metaphores³⁾. Just as visualizing Dick Fosbury prepare for a jump helped you understand the 10x Learning method.

Level 5: Make it Flow. Think about the order and direction of information, rearrange and draw arrows to visualize that direction. The flow of your mind map indicates what comes first and what comes next, what is a cause and what is an effect.

Level 6: Prioritize. Reflect on what is the most important. Make those ideas and arrows bigger. What if you had to explain this topic in 10 minutes? What would you include and what would you leave out? What if you only had 1 minute? What if only 10 seconds? These thought experiments help you evaluate what really matters, and produce high order thinking.

Once you’ve gone through these steps, you will have made the information extremely meaningful to you. And what is meaningful sticks in long-term memory¹¹⁾. You have built mental models out of information, which further triggers your curiosity, and after mapping these things out you may actually have more questions than when you started. The fact that you were able to come up with these questions reflects your improved understanding. You may have felt this yourself as you had an AHA-moment or two in the mind mapping process. If not, don’t worry. It takes practice - take it one step at a time.

Encoding for large amounts of information

In rare cases, you need to learn large amounts of information which do not inherently have a lot of meaning. For example, when I was learning Chinese characters, in a lot of cases I just had to know what they looked like. A long time ago, the strokes may have had a meaning which got lost over time.

In these cases, you may have to artificially add meaning to the information in order to make it stick.²⁴⁾

The memory palace (also called method of Loci) is a way of quickly adding meaning to information so you can remember it.

It leverages some unique properties of the human brain:

- Making the information spatial, allows you to use visual memory rather than formal memory to store the information²³⁾

- Creating a coherent and intriguing story to remember (since ancient times, humans have learned by telling stories)

- Make the information multi-sensual to leave a stronger impression

Example: everyone knows that the law of gravity was discovered by Isaac Newton, because of the meaning we’ve added to this discovery. He was sitting in his garden (spatial information), pondering the problems of physics. Then an apple fell on his head (ouch! multi-sensual), which made him realize that the earth and the apple were two bodies attracting each other due to gravity (a coherent story).

The memory palace method deserves a guide of its own⁴⁵⁾, but here are the basic steps of doing it:

- You have a list of items you need to remember (this can be anywhere between ten and thousands of items). If the list is not ordered yet, make sure that you find a logical order for it (again, preferably the order is meaningful, but in the worst case you can resort to an artificial order like alphabetical).

- Choose a space you’re familiar with, for example the house you grew up in.

- Now, imagine yourself at the entrance of the house. We will place an image representing the first item on the list there.

- Associate your item with an image that is as vivid, funny, bizarre, disgusting and multisensory as possible. The image should tell a short story (similar to Isaac Newton’s discovery of gravity). This makes your image memorable. Create as many associations as possible.

- Place this image at the entrance of the house. Maybe next to the mailbox, or inside the door opening. Again, really visualize it there, maybe even smell or hear it.

- Move to the next place in the house (maybe the hallway, or the shoe rack, or the coat hangers). You can take steps as small or big as you like, as long as it forms a logical route through the space. Repeat the process: associate the second item on your list with a vivid image, and place it along the route.

You can now recall all the list items by walking along the route you created in your head. You will “see” the weird images, and the only thing for you to do is translate the images back into the original meaning.

3. Consolidation

No levels here. Just let it simmer. Really, take a break and do nothing.

4. Retrieval

After you’ve given the new knowledge a few days to consolidate in your brain, it’s time to try retrieving the information. Retrieval practice leverages the testing effect: when you make your brain actively work to recall the information, connections are strengthened, and subsequent recall will be easier.⁸⁾

As with encoding, retrieval practice is only effective when you use higher order thinking skills.¹⁸⁾ Common practice like testing yourself on basic facts over and over again actually inhibits creating new memory cues (even it it’s spaced out over time).⁹⁾

Instead, a varied and challenging practice creates new retrieval cues on every review, so that you are able to use the information in many different contexts (including the context in which it will be asked at the test).

Level 1: Varied spaced repetition and active recall flashcards

Spaced repetition is a way of spacing out your reviews over time, to produce the best recall with the fewest reviews³⁶⁾. It is based on the forgetting curve, which describes how the brain forgets information over time.²⁵⁾

By reviewing information at increasing intervals, the forgetting curve can be flattened out²⁰⁾, especially when you actively prompt your brain to recall the information.³⁷⁾

However, there are some important caveats:

- If the information is not properly encoded, the decline of the forgetting curve will be very steep to begin with, and you will need a lot of reviews to flatten it. This is very time-consuming and can lead to flashcard fatigue.¹⁸⁾

- If you recall the same information using the same retrieval cue every time, this particular cue will be strengthened, but the formation of new retrieval cues will be inhibited. This means you will have trouble retrieving the information in any other context (including the context on the test). It is also boring, and inhibits higher order thinking.

To make spaced repetition and active recall work for you, you will need to ensure that you first take time to encode the information. Taking the time to create good flashcards is a way of doing that. In fact, writing good flashcards, similar to mind mapping, helps you encode information effectively⁴⁴⁾. Some guidelines for making good flashcards⁴⁶⁾:

- A single flashcards should focus on a single concept

- The question should be precise (vague questions don’t allow you to evaluate whether you got it right)

- The flashcards should be effortful, actively making your brain work (high cognitive load)

If you feel the need to use a pre-made deck of flashcards (not recommended for reasons that should be obvious by now), do not bulk add them to your reviews. Instead, add flashcards one-by-one, modifying each one to make it meaningful to you.

Ideally, vary the retrieval prompts over time²⁶⁾. Have several prompts for the same piece of information. After a few reviews, you’re likely more fluid with the information, and you can use that fluency to come up with new spaced repetition prompts.

Example: I create a flashcard based on transcription.

The first flashcard is a “bad” flashcard. The answer is vague, there is more than one topic asked.

This is a good flashcard. It is simple, one question is asked, and it requires more higher order thinking than just knowing a basic definition because it is asking a situation.

If there are practice problems for the topic you’re learning, these are a great way to vary your retrieval practice. Problem solving helps you apply the information in different contexts.⁴¹⁾

Another great way of varying your practice is interleaving: if you’re studying multiple topics at a time, review them together to discover new connections between them.²⁷⁾

You know your retrieval practice is well-balanced if you feel a bit challenged every time. Not just challenge in retrieving the piece of knowledge from memory, but also in thinking about it in a new context. This feeling of challenge is called desirable difficulty. It is desirable because it’s a sure sign that your brain is learning.

Level 2: Writing = Thinking

This way of reviewing is perfect for you if you have a knack for writing and note-taking. Every time you revise the information, write down your improved understanding. Ideally, use a note-taking tool like Traverse which allows you to link to other notes you’ve created in the past. That way, you create a network of notes over time, which reflect what is happening in your brain, similar to a mind map. If you want to be very systematic with this, you can use the Zettelkasten note-taking system.²⁸⁾

Example: The day after I learn transcription, I also learn about translation. I write down translation into a mindmap and connect it into what I knew about transcription. Now I’m really building my knowledge.

Level 3: Self-explanation

Self-explanation means explaining the topic to yourself in a way that makes sense.²⁹⁾ This is basically taking the map you created in the encoding process, and translating it into a format that can be easily communicated, such as a short text (for which you can use the notes you took at the previous level) or a short video.

Making it coherent helps you identify knowledge gaps, and you may need to do further studying in order to fill those gaps.

This is also called the Feynman method. Feynman famously stated that you have only understood a topic once you’re able to explain it to a 5 year old.

Example: Now that I’ve studied the central dogma I write it out in a way I can always understand.

Level 4: Learning by Teaching

The Feynman method can be taken further by using your self-explanation to teach others, whether it’s family or friends, or followers on social media.

The feedback they provide on your teaching helps you identify further which parts you master and which parts are still muddy in your brain³¹⁾. Make sure your teaching is not one long rant, but follows a clear flow with a logical start and end.

Example: Once I’ve finished teaching the Central Dogma to myself I explain the concept to my friend who is also studying for the MCAT. They like the analogy of English to Spanish!

Level 5: Deliberate Practice

Once you’ve identified your strong and weak points, you can set up a deliberate practice. The practice can either aim at getting even better at your strengths, or drilling down at your weak points (the latter being more common when studying for tests). A deliberate practice is a particular activity which you can do repeatedly over time which helps you get more fluent in the subject. For example, a deliberate practice could be to write a short essay about a particular aspect of the topic your learning, applied to a particular aspect of your life.

Example: To Practice the Central Dogma I search online for “Central Dogma MCAT Practice Questions” I complete 5 of them and evaluate what I’ve missed.

Level 6: Experiment

You can now experiment with bringing your knowledge into practice in different contexts. This will inevitably be difficult. You will make mistakes and fail. Failure is one of the strongest signals to the brain that rewiring is needed. Fear of failure actually blocks your brain from trying to find the optimal brain wiring. Once you learn to embrace failure, you can use failure intentionally to accelerate your learning. Setting up a feedback loop in which you apply your knowledge, and use success or failure to correct yourself, is the way to become so fluent in a topic that it becomes like intuition.

5. Reconsolidation

Like in the consolidation phase, take a break after every retrieval practice to give your head time and space to reconsolidate and make the necessary modifications to your brain wiring and mental representations.

Example: I make a point to stop studying for the MCAT every night at 5pm. This gives my mind a time to rest and process everything I’ve learned.

Your Training Schema for Success

Now you know what the method looks like, but bringing it into practice is a whole other thing.

You will face challenges, like feeling overwhelmed, and the end goal may seem far and out of reach. Don’t get discouraged, but take it one level at a time. Even if you just manage to do level 1 activities at each stage, you’re ahead of 90% of students who are still rolling.

Unfortunately, many of the tools commonly used for studying, like Notion and Google Docs, were not built with effective learning in mind - let alone based on learning science. This makes setting up a 10x Learning System unnecessarily hard.

We build a tool aimed exclusively at learning effectively. It guides you at every step, from planning your pre-study, to the 6 steps of effective encoding and a varied retrieval practice. If you want to be smarter than your peers, this is the tool for you. Get it at Traverse.link.

Like athletes plan their training schema for Olympic success a year in advance, this section is your training schema for getting to 10x learning.

Realistically, it will take time (months to years) and effort before you are able to leverage the full method. But continuing with your old “rolling” techniques will be cost you much more time and pain in the long run. The habits outlined here will help you stay motivated during the journey and ensure you progress little by little.

Lifestyle

Even the best technique won’t work if you don’t create an environment around it where it can flourish. Fosbury wouldn’t have won Olympic gold with his technique if he ate cupcakes all day, or spend his days in night clubs gulping tequilas.

Just like an athlete, you have to get in shape for learning, and create the right environment for it to happen.

Nutrition

Stay hydrated. Drinking lots of water helps you stay awake. Limit caffeine beverages like coffee or energy drink to 1-3 per day.

Eat regularly to stay focused. Avoid foods with lots of sugar as they’re inevitably followed by a sugar crash. Fruits, veggies and nuts are the best.³⁹⁾

Exercise

Exercise regularly (half an hour a day). Optimally, exercise 20 minutes before studying to improve your concentration.

And this doesn’t need to be high jumping or other Olympic-level exercise - in fact, simple long walks are also great for giving your brain time and space to process information.

Sleep & Breaks

Sleep and break are where real learning happens³⁾. All study activities we do are just to prime our brain for optimal deep processing during rest periods. Sleep is the ultimate rest period. This is why so often, when practicing a new skill (like ice-skating) for a day and barely making any progress, after a good nights sleep when you start off again suddenly you seem to have made a leap of progress.

Breaks during the day are just as important. Put “Do nothing” blocks in your calendar to ensure you take enough breaks.

Planning

Planning ahead is the key to any form of high performance and achievement. At the end of every day, make sure you have a plan for the next day. What are you going to learn, when, and how? Do you have any other commitments you need to take into consideration. Also, actively plan ‘Do nothing’ blocks in your calendar where you will be taking breaks to give your brain time to process.³⁹⁾

Set limits to avoid ensure your brain gets enough rest, for example: ‘no more studying after dinner’.

Then, at the end of the day, check off each item and evaluate if you were able to stick to your schedule.

Make reflection part of the process

Periodic reflection is crucial for improving your process. At the end of every week, you are taking a break in order to re-assess the direction you’re going. This prevents you from walking full speed but in the wrong direction, as you will be able to course-correct timely, which saves you a lot of time in the long run.

Reflection is especially important when things aren’t going well. By reflecting, you can turn every failure into a win, as you get a much clearer idea of what is it you need to work on next.

A great way of reflecting is using Kolb’s Experimential Learning Cycle⁴⁰⁾. It allows you to unlock the Transformative Power of Mistakes.

Here are the steps to reflect and correct:

Step 1: Experience

What did you experience this week? What were some good and bad things?

Example: I tried adding flow to my Physiology mind map but struggled

Step 2: Reflect

How did you feel about the experience? How did you react? How did others feel and react? Which circumstances (like stress, tiredness) affected the experience?

Example: I felt confused when choosing an entry point for adding flow. I chose one intuitively but later ended up with something non-logical. It stressed me out.

Step 3: Abstraction

How do you tend to feel and react to such experiences? Which of you habits and approaches affected the experience?

Example: I tend to want to finish things quickly and don’t give them enough conscious thought. This ended up taking more time than if I had given it some more thought in advance.

Step 4: Experimentation

What can you change next time? How can you avoid failing in the same way? You may still fail in a different way, but with every failure you learn and get closer to the truth.

Example: Next time, when I feel in a hurry I will exercise first to calm my mind down.

Kolb’s learning cycle helps you become intentional about which study technique you use it which time. Over time, you will get to know exactly why you’re using this technique, at which order of thinking it operates, and what you’ll need to do next.

Habits and Consistency

To consistently plan your days and week, and execute upon your plan, you need to make planning and learning into a habit.

To successfully build a habit, use the Kaizen way (popularized by James Clear and BJ Fogg)⁴²⁾:

- Start with an incredibly small habit

Example: I will open my calendar app at the end of each day

- Choose a cue for your habit. A cue is something you’re already doing, to which you can now attach your habit

Example: once I finish washing the dished for dinner, I’ll open my calendar app

- Make the habit attractive by creating a craving

Example: put a big red X on a physical calendar for every day you’ve done your planning

- Make the habit easy to ensure you can execute

Example: I will just put the #1 thing to do the next day in my calendar

- Reward yourself for successfully executing the habit

Example: once the day is planned, I can watch my favorite series

Procrastination

Here hides the #1 enemy of any student, researcher or knowledge worker: procrastination.

In order to beat procrastination, you need to track it first: what gets measured, gets improved.

When you do your daily reflection at the end of the day, evaluate which tasks you completed, and which ones you didn’t. If you didn’t, write down the reason. If it’s a weak reason like watching Netflix instead of reading, putting that down onto paper helps you identify the weakness, and makes it less likely that you will commit the same mistake again.³⁹⁾

Focus

Keeping your focus is hard in an age of distraction.

However, you can make it easier for yourself, for example by putting your phone in a different room when you’re studying. Or, it that’s too much, put it into gray-scale mode and you’ll notice those notification icons seem way less urgent.

In general, avoid multitasking at all times. Do one thing at a time and do it well. As the saying goes, half doing things is an expensive way of not doing them.

To create focused blocks of study in your day, us the Pomodoro method. You study concentratedly for 25 minutes, and then take a 5 minute break where you do something you enjoy. This is both a reward for your hard effort, and time for your brain to process the information you studied before.

Training your brain muscle

In order to keep pushing your learning limits, you need to train your brain muscle. Specifically, you need to increase your cognitive load tolerance.¹⁴⁾

You need to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.

You can do this by some of the steps described earlier:

- Deliberately delay your note-taking to force your brain to make sense of the information first

- Keep pushing yourself to get to higher and higher orders of thinking, progressing along the levels outlined above.

Recap

- Set up your system for higher order learning

- Encode information in a way that makes sense to you

- Take breaks and sleep to ensure the information is consolidated

- Set up a varied retrieval practice

- Embrace failure and unlock the power of mistakes

- Set up your training schema

- Maintain a healthy life style

- Plan each day and each week

- Reflect and evaluate

- Build the habit and train your brain muscle

What you should do next

That’s a lot of information. Remember, you only need to do one step at a time.

Choose a system you’re comfortable with (most existing tools can be made to work with some effort - or use our tailored learning tool Traverse.link), and aim to get just one level up from where you are now.

It is a lifelong journey - good luck!

If you found this guide helpful and are continuing to benefit from it, share it with friends and colleagues who may have the same struggles. It may be able to help them too, and it helps me teach the world how to learn.

Supporting Studies and Research

- Report on Learning: A Practical and Learner-Centric Perspective by Sung · 2022

- The Relation Between Students’ Effort and Monitoring Judgments During Learning: A Meta-analysis by Baars et al · 2020

- Learning How to Learn by Oakley · 2018

- Problem of Schooling by Wozniak · 2017

- The multi-store model of memory by Atkinson and Shiffrin · 1968

- The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information by Miller · 1956

- Make it Stick by Roediger & McDaniel · 2014

- Rethinking the Use of Tests: A Meta-Analysis of Practice Testing by Adesope et al. · 2017

- Impact of reducing intrinsic cognitive load on learning in a mathematical domain by Ayres · 2006

- Learning as a generative process by Wittrock · 2010

- A Systematic Review of Higher-Order Thinking by Visualizing its Structure Through HistCite and CiteSpace Software by Liu et al · 2021

- Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems by Conklin · 2005

- Human problem solving by Newell & Simon · 1972

- Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later by Sweller · 2016

- Perceiving effort as poor learning: The misinterpreted-effort hypothesis of how experienced effort and perceived learning relate to study strategy choice by Kirk-Johnson · 2019

- How and when do students use flashcards? by Wissman · 2012

- Everyday lessons from the science of learning by Lang · 2016

- Effects of self-explanation as a metacognitive strategy for solving mathematical word problems by Bielaczyc et al · 1995

- The Dunning–Kruger Effect: On Being Ignorant of One's Own Ignorance by Dunning · 2011

- A Meta-Analytic Review of the Benefit of Spacing out Retrieval Practice Episodes on Retention by Latimier · 2021

- Use Your Head by Buzan · 1974

- Chunks in expert memory: evidence for the magical number four ... or is it two? by Gobet & Clarkson · 2004

- Development of Theory of Mind and Executive Control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences by Lang et al · 1999

- Moonwalking with Einstein by Foer · 2011

- Über das Gedächtnis by Ebbinghaus · 1885

- Measurement of Cognitive Load in Instructional Research by Paas & Van Merriënboer · 1994

- The effects of interleaved practice by Taylor & Rohrer · 2009

- How to Take Smart Notes by Ahrens · 2017

- Learning how to use a computer-based concept-mapping tool: Self-explaining examples helps by Hilbert & Renkl · 2009

- Traditional and Inquiry-Based Learning Pedagogy by Khalaf · 2018

- Using elaborative interrogation by B Kahl · 1994

- Mind Mapping in Learning Models: A Tool to Improve Student Metacognitive Skills by Dyah Astriani · 2020

- The effect of mind-mapping applications on upper primary students’ success and inquiry-learning skills in science and environment education by Ali Günay Balım · 2013

- The Effect of Concept Mapping to Enhance Text Comprehension and Summarization by Chang · 2002

- The Random-Map Technique: Enhancing Mind-Mapping with a Conceptual Combination Technique to Foster Creative Potential by Charlotte P. Malycha · 2017

- Distributing Learning Over Time by HA Vlach · 2012

- Test-Enhanced Learning by Roediger & Karpicke · 2006

- Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques by Dunlosky · 2013

- How to become a Straight-A Student by Newport · 2006

- Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development by Kolb · 2002

- Cognitive skill acquisition by VanLehn · 1996

- Atomic Habits by James Clear · 2018

- How to Read a Book by Adler · 1940

- Augmenting Long-term Memory by Nielsen · 2018

- How to Create A Memory Palace by Metivier · 2022

- How to write good prompts: using spaced repetition to create understanding by Matuschak · 2020

- The picture superiority effect in recognition memory: A developmental study using the response signal procedure by Defeyter · 2009